- Telephone

- Email

On the 6th June 1875 James Venture Mulligan discovered tin ore in the Wild River near Herberton. He wrote in his journal that “there may be any quantity of it here, but what use is it at present in this wild place …” Mulligan was one of the early white explorers who trekked through this area, often traversed only by the Aboriginal people of the four main groups whose lands bordered each other here. He was driven by a search for mineral wealth – mainly gold. Another early settler, John Atherton, whose attention was mostly centred on cattle, directed a small party of which John Newell was a member, to the same site in November 1879. However they were not successful in finding payable quantities of ore and returned to the already established tin diggings at Tinaroo.

Rumours in early 1880 that Chinese miners were planning to move to a new find, revived the interest of several members of that earlier party. A group of four men from the Tinaroo Tinfield, William Jack, John Newell, Thomas Brandon and John Brown, on the assumption that the new find could be near the Wild River, returned to the area and this time found payable quantities of ore.

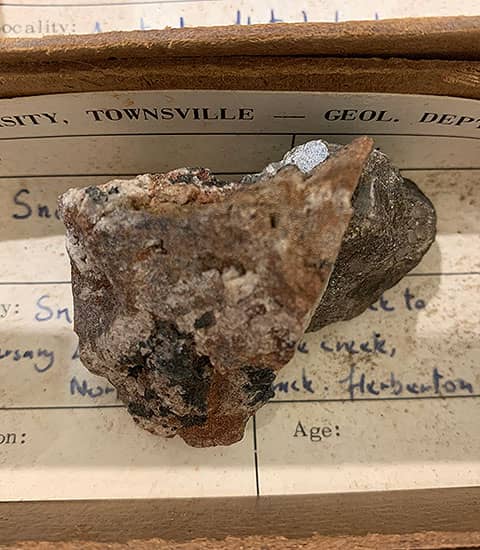

They traced the source of the ore up a small gully now locally known as Prospectors Gully (shown on some maps as the Great Northern Gully) and after initially failing to recognise the significance of the outcrops of black rocks, soon realised they were the discoverers of a major find. It was, in fact, lode tin, as distinct from alluvial ore, and one of the richest finds in Australia. The following day they posted notice of the claim. The date was 20th April 1880.

Local folklore tells of the smelting of some samples in a tree stump to verify what it was, followed by an epic overland ride by John Newell to Thornborough to lay claim to the find. The first mining operations actually commenced on the 8th May. By the end of that month, 100 tons of tin ore were stacked on the field. The first tin from Herberton arrived in Cairns on 17th July.

After Warden Mowbray laid out the town on 21st August, tents and bark huts began to give way to sturdier timber buildings. By 11th September, Herberton could boast one hotel, a butcher shop, and three stores, and the original discoverers had purchased a 60 acre (24 hectare) mining freehold they called the Great Northern. The first women arrived on the field about the same time with the coming of the Bimrose family, followed by the Arbouins, a week later.

John Moffat’s arrival in mid October 1880 saw the foundations laid for one of the North’s greatest mining empires. He quickly invested in the field and by November, machinery to treat the ore was on its way from Port Douglas. About the same time, the first mail service was begun from Cairns.

By Christmas of that year the field boasted a population of 300 men and 27 women. High expectations of a great future were ushered in with the skirl of the pipes, played by Hugh Harrison, a publican at the time, at a picnic on the banks of the Wild River, to mark the start of the New Year of 1881.

Expansion continued rapidly. During 1881 the School of Arts Committee was formed, first using a bark hut and soon thereafter the present building. Two newspapers vied for news. New hotels were built and a report lists licensees for twenty-four such establishments in the immediate district up to 1900. ‘Second to none of the first class hotels in the Colony’ was the grand Post Office Hotel, subsequently destroyed by fire in 1930.

At the end of 1881, Herberton became the seat of local government for the area with the formation of the Tinaroo Divisional Board. By 1888, the town’s importance had risen to the extent that the immediate area became a municipality with one of the founders of Herberton, John Newell, becoming first mayor. The municipality was subsumed into a larger area called the Herberton Divisional Board in 1895. Herberton remained the centre of local government for what was ultimately called the Shire of Herberton until amalgamation in March 2008. Herberton now forms part of the Tablelands Regional Council.

Meanwhile, mine after mine opened. In the hill behind the Mining Museum and near the Great Northern were the Wild Irishman, the Home Rule, the St Patrick, the Young American, the Erin-Go-Bragh, the Dawn of Hope, the Cornishman, the Southern Cross, the Irish National Land League, and the Soggoarth – to name but a few. The names are poignant hints of the origins of the miners as well as their hopes and fears. Two such hopes and fears were centred on transport problems and the original inhabitants of the area – the Aboriginal people.

The substantial wet of 1882 had shown how urgent was the need for reliable transport of life’s necessities into the area as well as movement of mineral production out to a coastal port. Trail blazing and agitation for a railway became dominant activities. Christie Palmerston and John Doyle are two notable pathfinders of these times. Ironically, while the choice of Cairns as the rail outlet and port for Herberton ensured the growth of that city, the railway did not reach Herberton until 1910 when the pioneering township had already begun a steady decline.

Herberton also did not escape the racial tensions of the time. The Aboriginal people did not appreciate the loss of living space nor the treatment they received at the hands of some whites. Consequently, in the first few years, a mailman was killed at Wondecla and two miners speared at Watsonville. A punitive expedition by the Nigger Creek Mounted Police remains a lasting memory of harsh treatment for descendants of those people. Tribal numbers were also reduced by relocation to Mona Mona Mission and the 1918 ‘flu epidemic.

The Chinese did make it to Herberton but mainly as gardeners, cooks and shopkeepers. A large population lived on the northern outskirts of Herberton until local agitation helped move them to Chinatown at Atherton. In fact, descendants of some Aboriginal people have strong family linkages with the early Chinese. The cultural bridge is even more pronounced, as a number of these descendants became well-respected miners in the white – dominated Herberton field.

Politics also exercised the minds of local people. Newell was member for Woothakata in the Queensland Parliament for two terms 1896 -1902 and thus saw in Federation. After some initial coolness to the proposal, he also had some involvement in the push for a new state in North Queensland. It should also be remembered that the vote from the mining fields of Herberton and Charters Towers was what tipped the balance for Queensland to support Federation, thus making the required majority of people and states in the referendum to see this dream become a reality.

What appeared to be Herberton’s death knell occurred in 1985 when formerly strategic stockpiles of tin metal were dumped on the world market. Price collapsed from $16,000 a tonne to $3,000. Herberton became near bankrupt overnight. Herbertonians are tough. The town shifted towards tourism. Now, suddenly, the price of tin has soared above A$40,000 a tonne and current tin prices can be found here. Perhaps the era has not ended.

Although Herberton has subsequently declined from its pre-eminent position as the premier township on the Atherton Tablelands, that decline has created a legacy of heritage unparalleled in Far North Queensland.

© Herberton Mining Museum History Association 2026